Down Syndrome Research Could Provide Important Insights Into Cancer Treatments

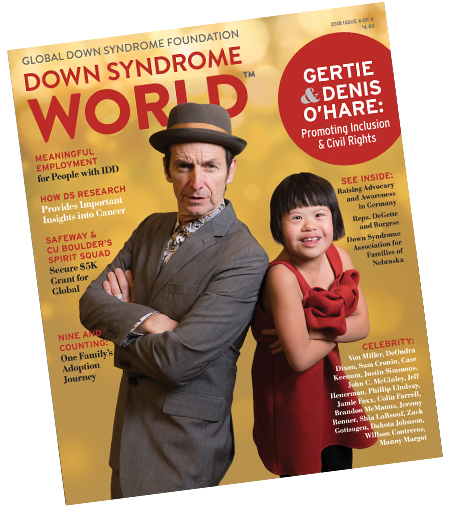

From Down Syndrome World Issue 4 2018

People with Down syndrome are highly protected from most solid tumor cancers, and yet they are highly predisposed to certain blood cancers. Studying people with Down syndrome may lead to new cancer treatments that could benefit everyone.

ACCORDING TO THE AMERICAN CANCER SOCIETY, an estimated 1,762,450 new cases of cancer will be diagnosed in 2019. There are hundreds of types of cancers and different ways to categorize them. One way to categorize cancer is into two types — solid tumor cancers and blood, or hematological, cancers.

People with Down syndrome are highly protected from most solid tumor cancers, such as breast, uterine, and prostate cancers. However, people with Down syndrome are much more likely to develop certain leukemias, one of the key blood cancers found predominantly in children.

IN SEARCH OF ANSWERS

World-renowned cancer researcher Joaquín Espinosa, Ph.D., Executive Director of the Linda Crnic Institute for Down Syndrome, has studied cancer biology for years. He was an early career scientist of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute before a grant from the Global Down Syndrome Foundation opened his eyes to the broad implications of investigating the connection between cancer and Down syndrome.

“My mentor, Tom Blumenthal, was the director of the Crnic Institute and insisted I apply for a grant,” says Dr. Espinosa. “I had no idea that the science would be so fascinating and that I would come to feel that people with Down syndrome are like my extended family.”

Three years later, Dr. Espinosa and his team discovered that the extra copy of chromosome 21 in people with Down syndrome triggers an immune system process called the interferon response, which may have a significant bearing on cancer risk.

“From birth, the immune system of people with Down syndrome is very dysregulated,” Dr. Espinosa says. “It’s out of balance, so aspects of it are hyperactive and others are weakened. The hyperactivity may explain why solid tumor cancers are not allowed to grow and, therefore, why it is rare for people with Down syndrome to get most solid tumor cancers. Conversely, it may also explain why autoimmune disorders are so prevalent.”

Other researchers hypothesize that chromosome 21 contains one or more tumor-suppressing genes, which may explain why having an extra copy of the chromosome protects against solid tumors, and that the chromosome also contains genes that spur the development of leukemias.

This article was published in the award-winning Down Syndrome World™ magazine. Become a member to read all the articles and get future issues delivered to your door!

This article was published in the award-winning Down Syndrome World™ magazine. Become a member to read all the articles and get future issues delivered to your door!

LUKEMIA: AN EARLY CHILDHOOD RISK

Children with Down syndrome are particularly susceptible to two types of leukemia: acute megakaryoblastic leukemia (AMKL) and B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (B ALL), the most common subtype of acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL).

They are also uniquely susceptible to one bone marrow disorder that results in a higher risk of AMKL called transient myeloproliferative disorder (TMD). TMD, also called transient leukemia, is found only in newborns with Down syndrome. As many as 30 percent of babies with Down syndrome are born with TMD, and although it can cause severe or life-threatening problems, the overwhelming majority of cases resolve naturally by the third month of life.

However, infants with TMD are at increased risk of developing acute myeloid leukemia (AML), which can strike children all the way through the teenage years. In particular, children with Down syndrome between ages 1 and 5 are 150 times more likely than typical children to develop AMKL, a rare type of AML. AMKL is a life threatening leukemia in which malignant megakaryoblasts proliferate abnormally and injure various tissues.

While the risk for AMKL is consider ably higher, many studies report better outcomes for patients with Down syndrome compared with their typical counterparts. Children with Down syndrome who develop AMKL have a roughly 80 percent five year event-free survival rate, which is substantially better than that seen in typical children with this leukemia, according toJohn Crispino, Ph.D., Robert I. Lurie, M.D. and Lora S. Lurie Professor of Medicine at Northwestern University.

“Nevertheless, not all children with Down syndrome survive the disease, and survival rates for those who relapse even after a bone marrow transplant are abysmal,” Dr. Crispino says.

Dr. Crispino’s lab has several areas of focus including acute leukemias and myeloproliferative neoplasms, and he is considered one of the leading authorities regarding leukemia in patients with Down syndrome.

According to Dr. Crispino, there is a 20-fold increased risk of B-ALL in children and young adults with Down syndrome primarily from ages 5 to 20. B-ALL is an aggressive type of leukemia in which too many B-cell lymphoblasts are found in the bone marrow and blood.

Unlike AMKL, reports and studies show that patients with Down syndrome with B-ALL fair worse than their typical counterparts — they have a higher relapse rate, may suffer severe side effects from chemotherapy, and have higher treatment-related mortality.

According to Dr. Crispino, part of the problem could be attributed to the attending physicians’ lack of adherence to the different chemotherapy protocols for pediatric patients with Down syndrome. Patients with Down syndrome often react poorly to standard chemotherapy for B-ALL, and their “toxicity profile” means more side effects that can result in extreme loss of red and white blood cells and platelets, inflammation in the digestive tract, and even heart failure.

“These patients need modified treatment protocols and universal supportive care guidelines that are optimal,” says Dr. Crispino. “Including patients with Down syndrome in studies of novel agents, such as immunotherapy and JAK inhibitors, could also help address this problem.”

Global’s lobbying and advocacy effor ts, resulting in a $24 million increase in Down syndrome research at the National Institutes of Health (NIH) in 2018, certainly led to an increase in cancer research in this special population, but there is still a long w ay to go. Dr. Crispino believes we desperately need less toxic and more effective therapies, especially to prevent relapse and treatment related mortality in patients with Down syndrome. He advocates for research at the NIH that would determine why Down syndrome leads to the increased incidence of leukemia and identify novel drug targets that will lead to development of safer treatments, and for leveraging new technologies that will identify specific genes on chromosome 21 linked to leukemia.

While leukemia does not always cause symptoms, Karen Rabin, M.D., Ph.D., Associate Professor of Pediatric Hematology/Oncology and Director of the Leukemia Program at Texas Children’s Cancer Center and Baylor College of Medicine, says parents should look out for bone pain, difficult y walking, easy bruising or bleeding, pallor, prolonged and unexplained fevers, and swollen glands in the neck and elsewhere.

A complete blood count can detect leukemia in some cases but is not recommended unless symptoms are present, according to Dr. Rabin. Chemotherapy is the standard treatment for most acute leukemia. But immunotherapy — a class of therapies that train the immune system to target cancer — is an emerging option.

“Immunotherapy is not generally used for newly diagnosed ALL at this time, but it is a very effective treatment in cases of relapse,” Dr. Rabin explains. “I particularly recommend early consideration of immunotherapy for relapsed ALL in children with Down syndrome because they are at high risk of serious complications when treated with standard relapse chemotherapy regimens.”

RESEARCH THAT BENEFITS EVERYONE

Of the 1.7 million new cancer cases estimated to be diagnosed in the United States in 2019, it is impossible to know how many of those cancers will occur in people with Down syndrome, according to Dr. Espinosa. Regardless, studying cancer in this population benefits anyone who develops the disease. Dr. Rabin agrees.

“We first discovered a major class of genetic alterations in ALL by studying ALL samples from children with Down syndrome, where the alterations are much more common than in other ALL cases,” she says. “This has led to a clinical trial of ruxolitinib, an inhibitor targeting this pathway, as a new treatment for ALL.”

Dr. Espinosa and his team at the Crnic Institute, with financial support from Global’s Mary Miller & Charlotte Fonfara-LaRose Down Syndrome & Leukemia Research Fund, are testing the effectiveness of drugs that inhibit two genetic mutations that cause runaway cellular growth linked to leukemia. Dr. Crispino and his team have conducted preclinical studies of inhibitors of a particular gene on chromosome 21 that may be active both in individuals with Down syndrome who have B-ALL and in some typical individuals with that type of leukemia.

“With respect to solid tumors, research into why people with Down syndrome develop cancer at low rates has enormous potential to shed light on chemoprevention strategies,” Dr. Crispino states. “If we can discover the genes on chromosome 21 that protect against solid tumors, we may be able to leverage these insights to develop drugs to halt cancer initiation or progression in all people.”

Like this article? Join Global Down Syndrome Foundation’s Membership program today to receive 4 issues of the quarterly award-winning publication, plus access to 4 seasonal educational Webinar Series, and eligibility to apply for Global’s Employment and Educational Grants.

Register today at downsyndromeworld.org!

Recent Posts

- Exclusive Interview with the Down Syndrome Coalition for El Paso President – Amelia Rau

- In Loving Memory of Quincy Jones

- Historic First Win: House Passes DeOndra Dixon INCLUDE Project Act

- Down Syndrome Regression Disorder vs a Mother’s Love: A Washington Post Mother’s Day Feature

- A Loving Tribute to Carla Gene Shankle

Experience our inspirational and groundbreaking videos and photos. Our children and self-advocates are beautiful AND brilliant!

Experience our inspirational and groundbreaking videos and photos. Our children and self-advocates are beautiful AND brilliant! Make sure your local Representatives are on the Congressional Down Syndrome Task Force.

Make sure your local Representatives are on the Congressional Down Syndrome Task Force.