What Parents Need to Know About Life Expectancy & Pediatric Medical Care

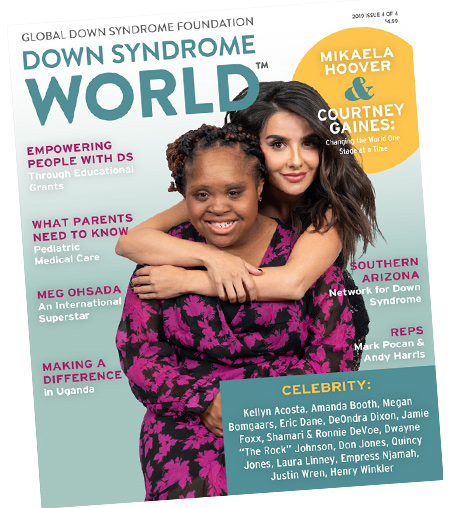

From Down Syndrome WorldTM 2019 Issue 4 of 4

Dr. Fran Hickey, a parent to a son with Down Syndrome with over 30 years experience caring for children with Down Syndrome, provides insights and important takeaways

This article was published in the award-winning Down Syndrome World™ magazine. Become a member to read all the articles and get future issues delivered to your door!

This article was published in the award-winning Down Syndrome World™ magazine. Become a member to read all the articles and get future issues delivered to your door! ACCORDING TO THE CENTERS FOR DISEASE CONTROL AND PREVENTION (CDC), approximately 6,000 people are born with Down syndrome in the United States every year. The average life expectancy of a person with Down syndrome has more than doubled since the 1980s – from 25 years to 60 years today. The dramatic increase in lifespan for people with Down syndrome over the last 30 odd years can be attributed to many factors. First, there was the dismantling of inhumane institutions in the 1980s and early 1990s where people with intellectual and developmental disabilities to be placed in institutions where they were not provided basic medical care, let alone life-saving procedures such as appendectomies or heart surgery. In fact, at the notorious Willowbrook State School on Staten Island, New York, there was no plumbing and residents were injected with diseases in an attempt to discover cures over a sixteen-year period. It was finally closed in 1987.

With deinstitutionalization came more inclusion at home, in schools, and eventually society – all of which also play a role in health outcomes. In addition, since an estimated 40-50% of children with Down syndrome are born with a congenital heart defect, another big factor leading to increased lifespan was advancement in cardiac repair and surgery.

While basic and even clinical research has languished for people with Down syndrome even until recently, medical care has progressed significantly over these same decades. An important resource that has made a substantial difference in health outcomes is the publication of Health Supervision for Children with Down Syndrome by the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP).

“The best thing a parent can do for their child with Down syndrome is to utilize the pediatric care guidelines set by American Academy of Pediatrics,” says Dr. Fran Hickey, a beloved Down syndrome expert and the medical director of the Anna and John J. Sie Center for Down Syndrome at Children’s Hospital Colorado.

The Sie Center, part of the Crnic Institute for Down Syndrome and an affiliate of the Global Down Syndrome Foundation, was established in November 2010 and now has nine weekly clinics including a feeding clinic, sleep clinic, education clinic, and mental wellness clinic. The center is also home to other renowned medical providers including Patricia C. Winders, PT; Dee Daniels, RN, MSN, CPNP; and Dr. Lina Patel, PsyD. Together, they serve over 1,800 patients from 28 states and 10 countries.

THE NEED FOR A DOWN SYNDROME-SPECIFIC RESOURCE

People with Down syndrome are born with three copies of chromosome 21 instead of two. The result is a dramatically different disease profile whereby people with Down syndrome are highly predisposed to certain diseases (e.g. Alzheimer’s disease and autoimmune diseases) and highly protected from others (e.g. solid tumor cancers, certain heart attacks and stroke). As such they require different medical care visits compared to those in the general population or other intellectual and developmental disabilities.

Despite being underfunded, the Down syndrome community has benefitted from the guidelines organized between 1981 and 1999 by dedicated clinicians, many from the Down Syndrome Medical Interest Group, who drew primarily on their vast experience with this patient population. Then in 2000, with the leadership of Dr. Marilyn Bull and many other contributors, the American Academy of Pediatrics used its resources, vast network, and peer reviewed vetting apparatus to create its first Health Supervision for Children with Down Syndrome. The guideline was last updated in 2011.

The AAP’s Health Supervision for Children with Down Syndrome is a comprehensive report of healthcare guidelines for children with Down syndrome from birth to 21 years of age. While it is designed for the pediatrician and subspecialists caring for child with Down syndrome, there is an 11-page family-friendly version also published by the AAP called “Health Care Information for Families of Children with Down Syndrome.”

A RENOWNED AND BELOVED DOCTOR

Dr. Hickey completed his undergraduate degree at Harvard University and his medical degree at University of Cincinnati College of Medicine, and his internship and residency at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital where he was mentored by Dr. Bonnie Patterson, a national leader in Down syndrome founded the renowned Thomas Center for Down Syndrome and DSMIG. Dr. Hickey is recognized as one of “America’s Top Doctors,” and has received numerous awards including the Maxwell J. Schleifer Distinguished Service Award from Exceptional Parenting Magazine, The Ross Award for Excellence in Ambulatory Pediatrics, the Senior Resident Teaching Award in Pediatrics, the Professional of the Year award, and Lifetime Achievement Award from the Down Syndrome Association of Greater Cincinnati. He and his wife Kris have four children, one of whom has the dual diagnosis of Down syndrome and autism.

Today, Dr. Hickey and his multi-disciplinary team of experts at the Sie Center for Down Syndrome at Children’s Hospital Colorado provide excellent medical care and conduct many research projects related to improving healthcare outcomes through improved medical care therapies, mental wellness and school interventions and therapies, as well as through applying the AAP Health Supervision for Children with Down Syndrome guidelines.

Dr. Hickey encourages parents to work closely with their medical team to determine the proper healthcare plan for their child’s specific needs. “Anyone who is providing care to a child or adolescent with Down syndrome should be aware of common co-occurring conditions and have a specific plan to monitor and evaluate the child’s health,” says Dr. Hickey.

As a supplement to the AAP pediatric guidelines, Dr. Hickey and his “Dream Team” of experts at the Sie Center have developed a simple one-page check-list and chart based on the AAP guidelines that lays out a roadmap of appointments, screenings, vaccines, and treatments. “The AAP has endorsed these guidelines to maximize the health of our children,” Dr. Hickey says. “They are so important to follow as long-term health guidelines and to allow children with Down syndrome to reach their health potential.”

“The AAP guidelines and Sie Center’s guidelines check-list are so important because they provide medical professionals a roadmap on how children with Down syndrome need different medical care,” says Michelle Sie Whitten, President & CEO of the Global Down Syndrome Foundation. “For example, a typical child may only get a hearing test if there is some evidence that child is not hearing. For children with Down syndrome who tend to have inner ear issues, they must get tested every year. You can imagine what not hearing does to our children’s lives.”

INSIGHTS AND TAKEAWAYS FROM DR. HICKEY

The AAP 2011 guidelines can be broken down into medical areas of focus and by age group. In september 2019, Dr. Hickey provided an informative webinar to over 100 attendees about the guidelines. Below are key insights and takeaways from Dr. Hickey’s webinar.

NEONATAL (BIRTH TO ONE MONTH)

In an infant’s first 24 hours of life, he/she will receive a physical examination for the state newborn screening, a public health service that tests for a variety of health disorders, including Down syndrome. If there was no prenatal testing and if the clinician feels enough criteria are present on physical examination to diagnose the baby with Down syndrome, then a blood sample should be sent for chromosome evaluation. Providing a diagnosis at birth should be done with care and counseling, and resources should be offered at the appropriate time.

There is a high rate of neonatal complications for newborns with Down syndrome; the overwhelming majority of which can be addressed and/or corrected. According to an article published by the Sie Center representing data from the Colorado mountain (an elevated region), an estimated 73% of newborns require a stay in a Neonatal Intensive Care Unit (NICU),which underscores the importance of appropriate medical readiness and intervention from birth to discharge. Well over half of these NICU stays are driven by additional oxygen needs, and approximately 60% require phototherapy to treat jaundice. Another driver of NICU stays are feeding problems which may require a nasogastric tube (NG tube).

CONGENITAL HEART DISEASE & PULMONARY HYPERTENSION

Congenital heart disease (CHD) and pulmonary hypertension (PH) go hand-in-hand. Since almost half of the babies with Down syndrome are born with a CHD, a newborn echocardiogram is imperative. This will show if and which exact heart abnormalities exist. In addition, every newborn should be evaluated for PH. PH compromises blood flow from the heart to the lungs due to tiny arteries in the lungs becoming narrowed, blocked or destroyed. This slowing or blockage of blood flow to the lungs puts undue stress on the heart.

An estimated 20% of 50% of babies with Down syndrome having CHD will need surgery within the first 4 months. The advancement of infant heart surgery has seen outcomes for all patients with CHD improve dramatically. Even with a more serious CHD that requires open heart surgery, the survival rate is well above 90% if caught in time.

Compared to the typical population with CHD, the prevalence of PH is still high. Signs to look for are hypoxia, polycythemia, obstructive sleep apnea, and feeding problems and aspiration. Keeping children with Down syndrome appropriately oxygenated is integral for prevention and treatment of PH.

HEARING

In the United States, all newborns get a newborn hearing screen. Approximately 20% of newborns with Down syndrome will initially fail. But only 2% have congenital hearing loss. The guidelines recommend a rescreen at 6 months with a Behavioral Audiogram. Hearing tests should continue every six months until 3 years of age after which children with Down syndrome should get their hearing tested annually.

An estimated 30-40% of infants with Down syndrome have stenotic ear canals (narrow ear canals), which makes it difficult to see the tympanic membrane and evaluate hearing. If a child with Down syndrome has stenotic ear canals, he/she should see an otolaryngologist or Ears, Nose, Throat (ENT) specialist for an otoscope with a microscope in order to avoid undiagnosed serous. otitis media and subsequent hearing loss. Clearly, hearing loss will not only impede the development of speech, but may also affect many other developmental milestones.

LEUKEMIA

Every newborn with Down syndrome should have a hematology test called a “complete blood count” (CBC). While only 2% of people with Down syndrome will have leukemia, this is still 10x or even 400x more frequent than in the typical population and more specialized treatments for children with Down syndrome are needed based on their. potentially different anatomical structure and reactions to medications.

Up to 30% of newborns with Down syndrome present with Transient Myeloproliferative Disorder (TMD). Twenty percent of those 30% will go on to get diagnosed with leukemia. Counseling the parents during such a diagnosis is very important. The two leukemia’s children with Down syndrome are more susceptible to are Acute Megakaryoblastic Leukemia (AMKL), a rare form of myeloid leukemia (ages 1-5), and B-cell Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia (ALL), a common childhood leukemia (primarily ages 5 to 20).

AUTOIMMUNE DISORDERS

It’s estimated that up to 70% of people with Down syndrome have one or more autoimmune disorder. At birth, babies have a newborn state screen that includes measuring thyroid with a test called T4. If a newborn fails this test, they will then have a thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH) test.

Because of the prevalence of autoimmune disorders (e.g. abnormal thyroid, hypothyroidism, diabetes mellitus, alopecia areata) the AAP guidelines recommend TSH screenings at 6, 12, and 18 months. Then starting at the age of 2, testing every year unless there are symptoms of thyroid dysfunction, in which case an immediate test should be administered.

The AAP guidelines have many other important recommendations including testing or obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) at 4 years old (or earlier if there are symptom). Over 60% of children with Down syndrome test positive to OSA whereby they are not breathing during certain times while sleeping. Respiratory illnesses are the cause of 80% of admissions to the hospital for children with Down syndrome, so mitigating exposure and treating ailments quickly is paramount.

The AAP guidelines cover ophthalmology, autism, gastrointestinal issues, and many other important areas. It is exciting to know that the AAP is working on an updated version, that will no doubt provide clinicians and families even more ways in which to ensure the good health of children with Down syndrome.

“While there are challenges, the developments in recent years paint a hopeful picture of medical care for people with Down syndrome, allowing us to help children reach their potential and enjoy their life,” says Dr. Hickey.

As a membership benefit, Global Down Syndrome Foundation hosts a quarterly webinar series on medical and educational topics such as Down syndrome research, healthcare, advocacy, and more. See a recap of Dr. Hickey’s September 2019 webinar on Pediatric Medical Care here: www.globaldownsyndrome.org/globalwebinar-series-fall-2019-recap/

Like this article? Join Global Down Syndrome Foundation’s Membership program today to receive 4 issues of the quarterly award-winning publication, plus access to 4 seasonal educational Webinar Series, and eligibility to apply for Global’s Employment and Educational Grants.

Register today at downsyndromeworld.org!

Recent Posts

- Clarissa Capuano & Midori Francis: Positivity & Authenticity

- Alex and Anthony: Out of the Box, Into the Spotlight

- GLOBAL LEADERS – An Exclusive Interview with Erin Suelmann, Executive Director of the Down Syndrome Association of Greater St. Louis

- Sleep Apnea Across the Lifespan in People with Down Syndrome

- Government Profiles: Robert Aderholt (R-AL) & Tammy Baldwin (D-WI)

Experience our inspirational and groundbreaking videos and photos. Our children and self-advocates are beautiful AND brilliant!

Experience our inspirational and groundbreaking videos and photos. Our children and self-advocates are beautiful AND brilliant! Make sure your local Representatives are on the Congressional Down Syndrome Task Force.

Make sure your local Representatives are on the Congressional Down Syndrome Task Force.