Founders’ Story

Grandparents Making a Difference

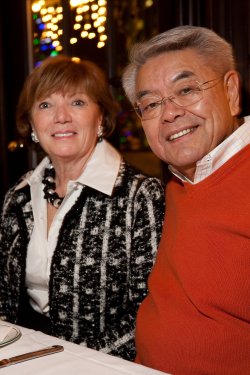

Anna Sie – Grandmother (Nonna in Italian)

“I want to make sure our granddaughter will benefit from anything we do. But that can’t happen if we don’t get to the bottom of these health issues for all people with Down syndrome. Helping my granddaughter, and the millions of others like her, is my mission and my passion in life.” – Anna Sie

John J. Sie – Grandfather (Ye Ye in Chinese)

“Eradicate is a harsh word. But it draws attention to what I mean – finding a conclusive solution. The goal is after 2017, the serious medical issues and cognition deficits for people with Down syndrome will be no more.” – John J. Sie

Anna and John J. Sie have a very different view on almost everything. “It goes beyond just being a man or woman, Chinese or Italian. We are sort of the epitome of ‘opposites attract’,” says John with a chuckle, about his marriage to Anna.

But there was one thing that Anna and John did see the same and that was the future of their granddaughter, who happens to have Down syndrome. When Anna and John’s daughter, Michelle, got her amnio results and broke the news to them that their granddaughter would have Down syndrome, it was like a revelation.

“We were going to love and nurture this baby no matter what.”

“Of course we were shocked at first, but it was as if the diagnosis itself instantly made us better people,” says Anna, who emigrated from Italy in the ‘50s with her father and brothers, settling in New Jersey. “We were in total agreement – we were going to love and nurture this baby no matter what.”

“And emotionally we had both been there. Being immigrants from Italy and China respectively and not speaking English, we were made fun of, people treated us differently, and life was quite challenging,” describes Anna. “This is not what we wanted for our granddaughter.”

“Because of our granddaughter we have a passion to help all people with Down syndrome,” says Anna (“Nonna” to her grandchildren). “This has become our life’s mission. We want the best for our granddaughter, but just as passionately, we want the best for all people with Down syndrome, young and old. As my husband says, from cradle to grave.”

“This has become our life’s mission. We want the best for our granddaughter, but just as passionately, we want the best for all people with Down syndrome, young and old. As my husband says, from cradle to grave.”

Wanting to support their daughter and son-in-law during their first child’s impending birth, the newly retired couple learned everything they could about the syndrome. “Unlike most families, we had an early diagnosis for our granddaughter,” says Anna. “So we had time to learn about it.”

But there wasn’t much information available about research, medical best practices or what was possible over the next horizon. What was the dream for our children? There were a lot of facts but few answers and many contradictions. The family was informed that Down syndrome is the “Cadillac” of disabilities, they were lucky their granddaughter was born in this century, and they should embrace a better future by helping to change society’s view of the disabled.

Because of his engineering mindset and entrepreneur’s optimism, John listened to the experts at hand, and then set his own course. “Throughout my life I have endeavored to see what was possible, regardless of conventional wisdom,” says John. “And then do the seemingly improbable.”

The father of five has a professional track record that speaks for itself. His first company, MicroState, was bought by Raytheon in the 1970s. Not to be held hostage by his engineering background, he helped launch the movie channel Showtime, as the head of marketing and sales. In the 1980s, John, a futurist, became enamored with cable television and helped build the then-largest cable TV operator, Tele-Communications, Inc. In 1991, he founded Starz Entertainment Group, launching first the Encore and later the Starz movie channels. Known as the godfather of digital television, John urged Congress and the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) to adopt digital high definition television (HDTV) as the standard – he wrote the first white paper on digital compression and almost single-handedly convinced Congress and the FCC not to adopt an analog HDTV standard that would have thwarted the growth that makes the US television market the largest in the world today.

Challenges are part of the fabric of John’s life. At the age of 14, John left war-torn China with his mother and two brothers. When his father was reunited with the family in the U.S., it was decided that John and his older brother would stay in the U.S. in a Catholic orphanage on Staten Island, N.Y., while his parents and younger brother got settled in Europe through a diplomatic posting. He lived in the orphanage until he graduated from high school. After receiving full scholarships, he earned a bachelor’s and master’s degree in electrical engineering.

John and Anna married and raised five children; living in New Jersey until 1984, when they moved to Colorado. The two immigrants, from entirely different cultures, came in search of a better life in America. Their blended clan is a melding of interests and international influences bound by the glue of family.

But nothing was easy, says their daughter, Michelle. “I remember both my parents working long hours – my mom managing the home, and my dad constantly traveling for his business. But we are immigrants, we don’t expect things to be easy and we know how to work hard.”

Though retired, the Sies tackled the issues around Down syndrome with their customary gusto. John was concerned about what could be done through research and Anna wanted to provide immediate medical care and programs for the children. John’s attitude towards Down syndrome was no different from any other intellectual puzzle he had encountered in engineering or business. He started from the ground up, going directly to geneticists and molecular biologists with his questions.

Tom Cech, Nobel Laureate

In 2006, the Sies organized a summit gathering some of the world’s best scientists, including Nobel Laureate Tom Cech, to explore the possibility of break-through research for people with Down syndrome. Many of the scientists were skeptical about just how much could be done through science to improve the lives of people with Down syndrome. But at the end of the summit, the scientists had two major reactions: (1) shock that Down syndrome was the least funded genetic condition by the National Institutes of Health, and (2) confidence that given recent advances in science and technology, measurable breakthrough for people with Down syndrome could be accomplished in a short period of time with appropriate levels of funding. The scientists, who gathered for the summit held at the University of Colorado at Boulder, gave the Sies hope.

That same year, the idea of the first academic home for Down syndrome research was born.

In 2008, the Sies’ family foundation, the Anna and John J. Sie Foundation became the founding donor of the リンダ・クルニック・ダウン症研究所. The Crnic Institute is the first in the United States to identify basic, clinical, and developmental research, alongside medical care for people with Down syndrome, as its core focus. The mission of the Crnic Institute is to eradicate the medical and cognitive ill effects associated with the genetic disorder. The partners of the Crnic Institute are the University of Colorado Denver School of Medicine, the University of Colorado Boulder そして Children’s Hospital Colorado.

The Crnic Institute is named after Dr. Linda Crnic, the former Director of what is today known as the Intellectual and Developmental Disability Research Center in Colorado. A renowned scientist in the field of Fragile X, Dr. Crnic had started to focus her talents on research for people with Down syndrome before her life was tragically cut short by a biking accident. Dr. Crnic mentored the Sies and their daughter Michelle in identifying the challenges and opportunities associated with funding for such research. She also introduced the Sies to most of the prominent scientists working on research for people with Down syndrome. After Dr. Crnic’s death in September of 2004, the Sies thought it befitting to name the institute after her. “She really cared about our kids first. The science was truly a means to end with Linda,” shared Anna.

Part of the process of making people with Down syndrome come first for the Sies was ensuring that the science addressed medical issues associated with the condition. An integral part of the Crnic Institute is the アンナ・アンド・ジョン・J・シエ・ダウン症候群センター.

“Anna wanted medical care and programs, I was more interested in the science. Happily, our daughter’s due diligence proved that both were essential in order to make a seismic paradigm change for people with Down syndrome,” says John. The Sie Center is the result of a year of due diligence on existing best practices and is a direct response to Anna’s desire to provide the best medical care and create programs for people with Down syndrome. The Sie Center has a world-class team of Down syndrome experts providing medical care as well as conducting clinical research.

“Most of the investment regarding Down syndrome research from the pharmaceuticals and medical community has been focused on early detection and termination,” says John. “But there are over 400,000 people with Down syndrome in the US and millions world-wide living today that need their human and civil rights addressed.”

John set a target date of 2017 to complete the mission of the Crnic Institute: eradicating the cognitive and medical deficits associated with Down syndrome. “It’s an audacious goal,” says John, who says he set the date of 2017, for selfish reasons. “I want to see the results in my lifetime.” If they reach their goal, people with Down syndrome will no longer suffer from sleep apnea, the early-onset of Alzheimer’s, or cognitive deficits.

Anna knew research would take time, and while she wholeheartedly supported the efforts, she wanted more immediate help. She was concerned that most doctors knew little about Down syndrome, and she wanted children with the condition to receive the best care from physicians and staff focused on the syndrome. She wanted accurate and unbiased information provided to women with a prenatal diagnosis of Down syndrome. And she wanted programs – and lots of them. “Why was it so hard to find a good music class, dance class, sports team or anything else for our children? Good teachers and good coaches can and do teach to all abilities. The issues I was hearing from other parents and grandparents didn’t make sense to me. I wanted to turn everything upside down. I wanted the families of children with Down syndrome to decide what program would be so privileged to have their child – not what ‘Downs kid’ was lucky to get into some program.”

Her staunch beliefs led to the creation of the “Dare To” classes under the Sie Center, a Denver Zoo internship program for people who have Down Syndrome, and the ALIVE Life-skills classes at the University of Denver for adults with Down syndrome.

Much of Anna’s passion surrounding the welfare of children with Down syndrome stems from her own experience. When she arrived in the United States with her father and brothers, she shouldered the responsibilities of caring for her family. At the age of 11, she was already starting to manage a household. She did not have the opportunities that most of her American friends and classmates had, including going to college. “As a girl in an immigrant family, I know what it is like when people have low expectations for you. When doctors don’t bother to get you real answers, when teachers won’t teach, these are all just examples of low expectations.”

Part of launching the Crnic Institute was establishing the fundraising, advocacy and education arm for the Crnic Institute – the Global Down Syndrome Foundation. The Sies’ daughter, Michelle, established the Global Down Syndrome Foundation in 2009 and applies the same laser focus and intelligence to her work as her parents do. “We’re proud of what Michelle and her Foundation are doing. Especially around the gross inadequacy of funding for research for people with Down syndrome from the National Institutes of Health (NIH). Last year the NIH budget was $31 billion and only 0.0007 went to research for people with Down syndrome. Even within the developmental disability category we are by far the least-funded,” says John.

Part of launching the Crnic Institute was establishing the fundraising, advocacy and education arm for the Crnic Institute – the Global Down Syndrome Foundation. The Sies’ daughter, Michelle, established the Global Down Syndrome Foundation in 2009 and applies the same laser focus and intelligence to her work as her parents do. “We’re proud of what Michelle and her Foundation are doing. Especially around the gross inadequacy of funding for research for people with Down syndrome from the National Institutes of Health (NIH). Last year the NIH budget was $31 billion and only 0.0007 went to research for people with Down syndrome. Even within the developmental disability category we are by far the least-funded,” says John.

Anna jumps in, “Fundraising and advocacy is a big part of what the Global Down Syndrome Foundation does. Of course, I don’t think any of us are really comfortable asking people for donations. But raising critical funds is the only way to truly create a brighter future for our children with Down syndrome. Every time John and I make that phone call for a donation, I think about those low expectations I grew up with, then I think ‘not on my watch’ and I make the call.”

感動的で画期的なビデオや写真をご覧ください。私たちの子どもたちや自己擁護者たちは美しく、そして輝いています!

感動的で画期的なビデオや写真をご覧ください。私たちの子どもたちや自己擁護者たちは美しく、そして輝いています! あなたの地域の下院議員が、米国議会のダウン症対策委員会(Congressional Down Syndrome Task Force)に参加していることを確認してください。

あなたの地域の下院議員が、米国議会のダウン症対策委員会(Congressional Down Syndrome Task Force)に参加していることを確認してください。